|

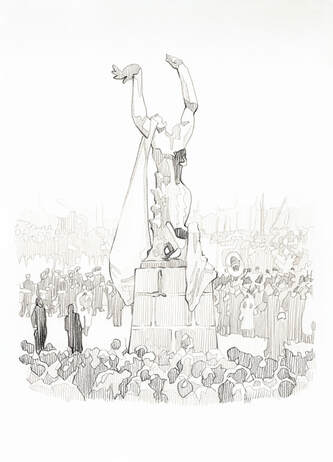

We invite you to engage with the work of our resident artists by visiting The Fragile Power of Drawing - a virtual residency exhibition, presented as part of the 2020/21 Drawing Research Program. Join Dulce as she shares her research from her studio in Mexico, while virtually transporting us to the Paris studio-museums through this Q&A series with curator Rahma Khazam. What drew you particularly to Ossip Zadkine’s The Destroyed City (1953), as opposed to his other works?

Your work frequently addresses memory and the reconstruction of events: how does this series fit within your work as a whole?

I do like to focus on reconstruction of events but particularly on those related to human challenges and tragic moments, because they fix the collective memory of a community. Remembering those kind of moments are important for our surviving and we learn from them. The unveiling of the monument was an important event for Rotterdam city because it generated a lot of questions from the people. This sculpture connected with the lived experience of each of their inhabitants and not just offering an aesthetic experience. That was the reason for all the expectation around it. Personally, I consider important the connection with the audience as part of the work so what Zadkine did is for me an example of this connection that I pursue. I dare to think that the main work happened that day of the unveiling was the connection with the public, the sculpture is just an excuse. What is special about drawing for you? Drawing is the main arena in which fiction can be mixed with factual reality, opening the opportunity to the speculation. It is a language that allows me to learn, to understand life, to ask questions and communicate through it. About Dulce Chacón Visit the exhibition online for more video and text conversations with the participating artists.

0 Comments

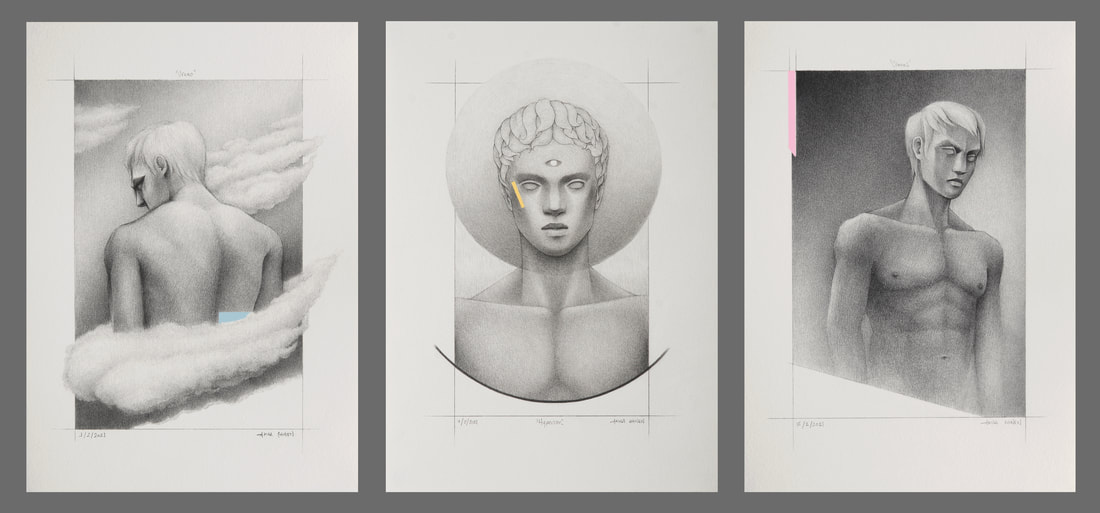

We invite you to engage with the work of our resident artists by visiting The Fragile Power of Drawing - a virtual residency exhibition, presented as part of the 2020/21 Drawing Research Program. Join Akira as he shares his research from his studios in Peru, while virtually transporting us to the Paris studio-museums through this Q&A series with curator Rahma Khazam. Why did you choose to respond to the work of Antoine Bourdelle? I found a better connection between my drawings and Bourdelle's work in the way he modifies the human figure. I love the primitivism of Zadkine, and the elegant volumes of Chana Orloff, but right now I feel more classical. I feel that we need "beauty" and "aletheia" more than ever. Aletheia as Esther Díaz's interpretation, in which one compenetrates with the artwork at the point that we forget ourselves overshadowing our problems as art discloses itself. The Titans Series: Urano, Hyperion, Cronos - Akira Chinen, 2021 How do you see the relation between your work and classical sculpture in general? Are you revisiting or updating its themes, and if so, in what way?

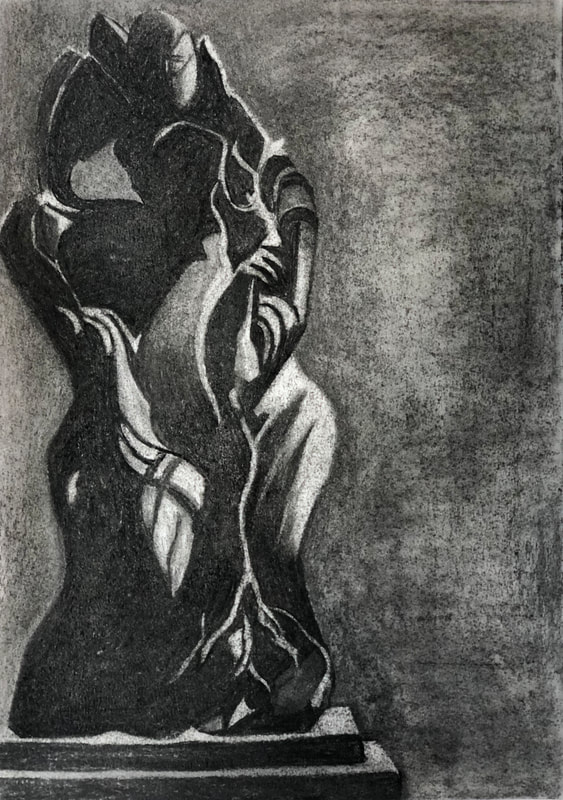

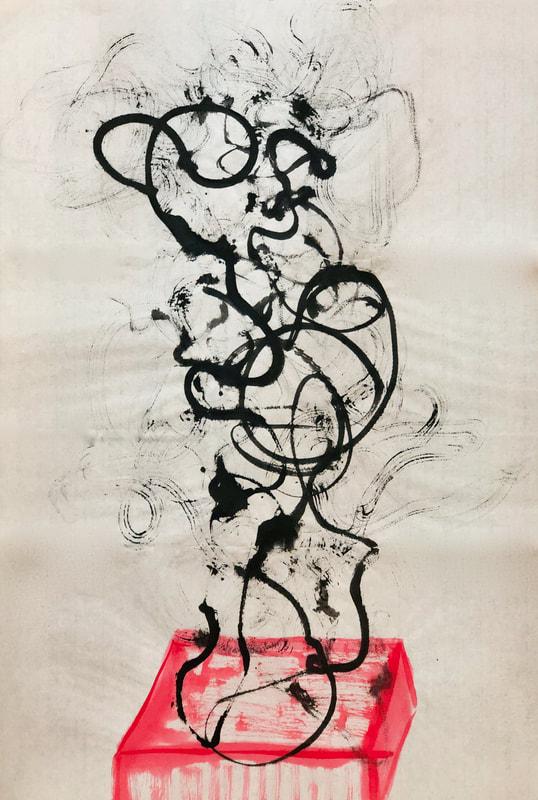

I studied at the school of fine arts of Perú, there we have excellent copies of many classical sculptures, although at that time I was more interested in exploring new mediums. I started my career as a "superflatish" artist but then I discovered zen and shinto, and suddenly I found myself drawing more spiritual things. In 2017 I visited Paris and looking at classical art, impressionism and post impressionism paintings sealed my interest in the spiritual sense those artworks gave me. This is how I feel right now and maybe I'll change my mind in a couple of years. I'm taking some of the same themes and visual references from Bourdelle, and of course I also looked after some storytelling between the pieces to talk about the circularity of life. As we know, Uranus trapped his sons but later got overthrown by one of them, Cronus, who also got overthrown by Zeus. And finally we have Hyperion as a depiction of someone who can only watch the reality and is in the middle, a witness who cannot act, maybe overwhelmed by the excess of information. He has no arms, and has his eyes shut. This is how I feel right now between the politics in Perú in the middle of a global pandemic. What is special about drawing for you? I think it is more direct and sincere. I look at drawing as an acoustic concert, or an acapella chorus. It is the most intimate approach with the artist and one of the oldest forms of human expression. I'm amazed what I can discover by repeating something as humble as lines on a flat surface. About Akira Chinen Visit the exhibition online for more video and text conversations with the participating artists. We invite you to engage with the work of our resident artists by visiting The Fragile Power of Drawing - a virtual residency exhibition, presented as part of the 2020/21 Drawing Research Program. Join Dipali as she shares her research from her studio in Malaysia, while virtually transporting us to the Paris studio-museums through this Q&A series with curator Rahma Khazam. What attracted you to Ossip Zadkine's sculptures of Venus? Venus is the goddess of love in Roman mythology. Ossip Zadkine’s sculptures of Venus encouraged me to investigate perceptions of love, its connotation as goddess in our current society and the relationship of love with sexuality. My own art practice incorporates some of these explorations. Through the materiality of sex toys which I associate as a symbol of female sexual liberation, my art deliberates notions of female sexuality and female sexual pleasure. I was curious to explore re-interpretations of the goddess of love just like Zadkine had done in his time with his expertise. When one thinks of the Birth of Venus one cannot help but think of the creation by the famous Italian artist Sandro Botticelli in 1480s. The colourful painting representing the goddess of love arriving to shore, in full nudity flanked by Zephyr, the god of wind on one side and the goddess (hora) of spring on the other. Zadkine’s Birth of Venus is very dissimilar to this original representation. Zadkine as a sculptor casts his representation in bronze. The change in medium from painting to sculpture brings about a shift in forms and textures. The artist’s interpretation of the idea based on the strength of his skill and the conviction of owning his concept despite the limitations that he may encounter inspired me to attempt several versions of my own. Donna Haraway ends her essay, The Cyborg Manifesto with the line “… I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess.” Here she is referring to the idea of women existing in the world as cybernetic assemblages of human and machine in order to subvert global androcentric mechanisms. This tension between becoming cyborg which is an integral part of my art practice and the goddess of love which has been extensively decoded by famous artists attracted me to reinterpret Zadkine’s Venus. These are two almost opposite approaches to drawing. One is a more figurative charcoal drawing, while the second is more abstract and experimental. Could you explain this contrast and relation between the two?

What is special about drawing for you?

In today’s fast paced virtual lifestyle, Drawing allows me to slow down and move slowly through time bringing me into the present in both mind and body. It creates space for me to observe intently and transpose my interpretations onto paper. The movements of the hands are different as compared to the constant typing on the keyboard, a refreshing break from mundane virtuality. The feel of materials on the dermis of my palms and the marks created through gestures and movements feel far more satisfying than the constricted sitting postures performed in front of cold blue LED screen of my laptop. There is also a special feeling drawing with machines (referring to my vibrator drawings). It is like action drawing where the control is limited, and a lot is left to chance. The end result is not more important than the process of creating the work. It is performative in nature as the movement of body in fusion with the device creates marks that are open to interpretation, breaking conventions and creating space for new imaginations. About Dipali Gupta Visit the exhibition online for more video and text conversations with the participating artists. We invite you to engage with the work of our resident artists by visiting The Fragile Power of Drawing - a virtual residency exhibition, presented as part of the 2020/21 Drawing Research Program. Join Hannah as she shares her research from her studio in Los Angeles, while virtually transporting us to the Paris studio-museums through this Q&A series with curator Rahma Khazam. How do you see the relation between your anatomical drawings and the work of Chana Orloff, Ossip Zadkine and Antoine Bourdelle? Chana Orloff, Ossip Zadkine, and Antoine Bourdelle all worked in the realms of figurative art which meant that they most likely had studied the human form extensively and also anatomically. As an educator I’m interested in how artists have historically learned their craft, and I find the best learning happens in an interdisciplinary practice. Even though these artists were working on creating the human exterior, in order to understand that one needs to understand what’s underneath the skin. There’s a good chance these artists studied the anatomy of the human body and drew it extensively in order to master figurative sculpting! Object in Inferior View (pink one in progress, blue is finished), Hannah Stahulak, 2021 While your work is realistic in nature, I like the way you've combined realism and abstraction. Could you talk about how you apply these ideas in these and other works of yours? And especially the tension between realism and abstraction?

I like balancing between the realms of realism and abstraction. Some people see my work as realistic and others have no idea what they are looking at (which I get a kick out of). When I was in school, I really struggled with which camp I fell into, and then realized I can be both. As a person I don’t feel like I’ve ever belonged in only one category, so why should my artwork? In terms of creating, I do usually start with a reference image (usually medical) of some kind. However I am selective with what I use in the reference image, it might only be a portion of an entire image. My drawings usually have no context or background either which can also leave them feeling abstract. I like leaving a lot up to the viewer, the idea I had going into a drawing does not need to be what the viewer gets out of it. I’ve valued artists like Georgia O'Keeffe whose references are from reality yet the viewer gets lost in what they are seeing. Abstract stems from realism, you’re choosing to change parts of it, you don’t need to lose the whole thing. What is special about drawing for you? Drawing is special for me in many ways, but I think the first thing that comes to mind is how drawing is built into every one of us. Some of our earliest records in history are drawn images. From when children are first given a pencil, they know what to do. Drawing is one of the most natural things I think we can do. I’ve always gotten so much satisfaction from drawing, it feels like home to me. It’s a way for me to process my world, my surroundings, my feelings, whether directly or indirectly. To know and love drawing is to have a deep level of connection to yourself and your surroundings. Drawing has in the past been overshadowed by mediums such as painting or sculpture, but it’s at the base of both those practices. I think all good artists have a solid foundation in drawing, because when you can draw you can create anything. About Hannah Stahulak Visit the exhibition online for more video and text conversations with the participating artists. |

keep in Touch!News and resources shared on this community platform are meant to further the engagement, stimulate active thinking, and create pathways for knowledge transfer and cross-cultural exchange. Archives

July 2024

CategoriesCover Image: L'AiR Arts residents, Multidisciplinary Program, January 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed